The Past Within review – Rusty Lake presents a short, surreal co-op puzzler

- 0 Comments

When scientist Albert Vanderboom passes away, it’s up to his daughter Rose to resurrect him. Or rather, two versions of Rose almost sixty years apart. In Rusty Lake’s 2D/3D point-and-click co-op adventure The Past Within, two players take on the role of the bereaved daughter – one in 1926, shortly after the death of her father, and the other decades later in 1984. It’s a quirky, surreal experience filled with a great many pattern-matching puzzles that revolve around a room, a box, and a shadowy figure, along with a bit of light grave robbing. While the story elements are thin and the one-character-in-different-time-periods notion isn’t really fleshed out at all, there’s a decent amount of fun to be had communicating solutions back and forth with your partner.

When The Past Within first starts, the two players must decide who will play in 1926 and who will play in 1984, referred to simply as “The Past” and “The Future.” There’s no actual time travel involved, just communication between young Rose in the twenties and old Rose in the eighties. Not that it really matters, as it doesn’t have much narrative impact. She could just as easily be two separate characters in neighbouring office buildings. What does matter is that your decision not only determines each person’s time period but how they will play and perceive the game.

In 1926, player A is in a single rather nondescript room with a locked dresser, a stained glass door leading to a closet, an old coal-burning stove, and Albert’s coffin, which is initially not openable. Within this space, the player can discretely turn in ninety-degree increments and view the surroundings as a series of 2D scenes, much like one of the developer’s Rusty Lake games. Player B, in 1984, is also in a single room, although this one is presented in real-time 3D. However, instead of moving freely about the location, this player’s view is fixed on a mysterious mechanical box set atop a table. The game controls allow for orbiting around the box, zooming in on its faces and interacting with the devices attached there.

Halfway through the game, these presentation styles flip, such that player A, still in 1926, gets to work with a 3D box on a table and player B, in 1984, can now move about their room in slideshow fashion with ninety-degree turning. At this point, player B can access a work desk as well as a couple of large, boxy medical machines for use in the resurrection process. No reason is ever provided for the swapping of perspectives, but it has the nice effect of shaking up the gameplay before it has any chance to start to feel repetitive.

Events kick off when 1926 Rose finds a letter in her room from her recently deceased father Albert. He details how, over the last couple of months, he’s built a device that allows for contact to be made with someone in the future. Albert hints that although he may be dead, this is not a permanent condition and can be reversed with help from the future. As it turns out, the device in question is the cubical machine that 1984 Rose has access to. So before both players can get on with the work of bringing Albert back to life, they must prepare the room in 1926 by performing a series of unusual tasks to help with the resurrection.

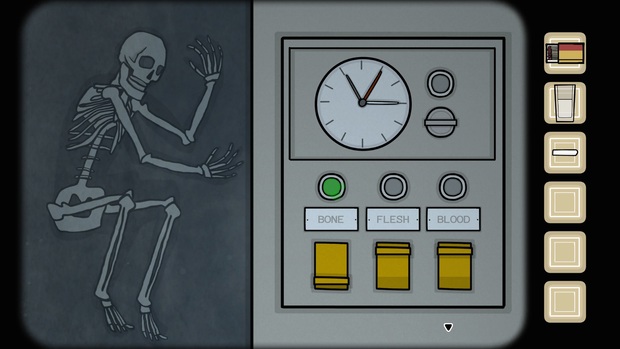

At one point a more macabre goal is introduced: to revive Albert, you must collect flesh, blood, and bone from his corpse. It’s only at this point that the game allows Albert’s coffin to be opened, providing access to the needed body parts. Extracting said parts is not a straightforward process, of course, and the puzzles involved in doing so make up the bulk of the gameplay. Once a given piece has been taken, it can be placed in the 1926 box to send it to 1984. There, older Rose must work with the lab equipment she has available to complete the resurrection process. For those squeamish around the sight of blood, the game’s cartoony style means that the harvesting of his various bits and bobs is quite clean and not too gruesomely depicted.

Whether in the past or the future, the visuals have a hand-drawn quality to them, with thick black outlines and clean, subdued colouring. In 1926, the furnishings, the walls, and the scant décor are depicted in browns, reds, and oranges, while 1984 features more blues and greys. It’s a simple style that mostly works well, although there are a handful of instances in the 2D world where it’s not always apparent what’s being shown. Is that square with other little squares a calculator? A set of storage boxes? A drawing of an apartment building?

There are no voices in The Past Within, but there is some occasional music. Although calling it “music” might be overstating a bit, as the tunes that play consist of short runs of notes like you might get from someone daydreaming at a piano and idly hitting keys. Sound effects largely remain in the background with various clicks, scrapes, and pings to provide some feedback when you interact with something. The audio neither adds to nor detracts from the experience, and will largely be ignored in any case as players need to be talking over it in constant communication throughout.

Although there is a little backstory concerning Rose, Albert, and the mysterious 3D box that allows communication between 1926 and 1984, the focus of the experience is on the puzzles. The challenges almost entirely consist of one player or the other finding a pattern or code of some sort and communicating it to their partner. For example, one player may have a diagram showing the directions that a handful of switches need to be toggled. They must communicate those details to the other player to correctly input on a switchboard.

Nearly all of the puzzles boil down to relaying patterns, but it’s a testament to how well dressed these challenges are that the game never feels repetitive (although the short two-hour run time probably helps as well). Some patterns are letters and numbers that need to be entered into certain devices, others are like the switches that need to be thrown, and some are really out there, such as counting across the teeth of Albert’s corpse to wiggle certain ones in a correct order. None of the obstacles are especially difficult and some can even be brute-forced by one player before the other finds the solution to provide. Fortunately, most tasks require enough information to be relayed or have too many possible combinations for a single player to push through their side entirely unaided.

Many of the puzzles would feel at best arbitrary and at worst random in a single player game. However, The Past Within gets away with it through the conceit of the cubical box. The 1984 version has a CRT display and the 1926 version a roll of paper that is able to convey instructions on what to do, such as “Person in The Future places black cube in C-9. Communicate code.” There’s no attempt to articulate why you’re doing what you’re doing; you’re simply carrying out advanced instructions you don’t really understand. As you progress, you will learn a little more about what Albert was up to with his research and the work he did on the 3D box. However, the full details of why he died, how he communicated with 1984 from 1926, how he knew to prepare the box in anticipation of his death, or even why his coffin is in the 1926 room are never made clear. This leaves a sense of puzzlement as to what just happened even when the game is completed.

In an effort to give a degree of replayability, at the start you can choose to follow either the path of a bee or a butterfly together. This selection doesn’t affect the narrative or any of the actual puzzles encountered, but it does change the patterns that must be entered. Coupled with the ability for either partner to start in 1926 or 1984, it does offer a chance to explore the other time period with different clues on a subsequent playthrough. That said, while my friend and I had fun with the game and enjoyed it as a nice little substitute to watching a movie, neither of us felt overly compelled to play it a second time.

Final Verdict

The Past Within is a short and fairly sweet two-player game, good for killing an evening – or two if you choose to reverse roles for a replay. The difficulty of the gameplay depends solely on your ability to communicate with your partner, with none of the puzzles themselves being intrinsically hard to solve, resulting in a noticeably short playtime for a single playthrough. The story aspect could have been better realized and the ending less of a head-scratcher, but overall it’s a solidly executed two-player co-op game, albeit one that’s likely to be quickly forgotten afterwards.

Hot take

Though it may not leave a lasting impression, Rusty Lake’s macabre The Past Within is a short but reasonably enjoyable two-player co-op experience about raising the dead through puzzles.

Pros

- Pattern-matching puzzles never feel repetitive

- Switching visual presentation styles halfway through keeps things fresh

- Option to change puzzle solutions on a second playthrough

Cons

- Flat 2D graphics section sometimes makes it difficult to tell what’s being depicted

- Dual time period concept is underutilized

- Ending has a “what just happened?” feeling

Richard played The Past Within on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment