Agatha Christie – Hercule Poirot: The London Case review – Sequel not quite vintage Queen of Crime, but c’est bon

- 1 Comment

Agatha Christie died half a century ago, but her work lives on. (Which is more than can be said of Roger Ackroyd, Lord Edgware, Mrs. McGinty, or several hundred other people stabbed, strangled, shot, bludgeoned, or poisoned by this respectable English lady.) Certainly her most famous detective, Hercule Poirot, he of the little grey cells and the big moustaches, is as busy as ever. In cinemas, the latest Kenneth Branagh vehicle (a surprisingly good adaptation of a late-period, and far from great, novel, Hallowe’en Party) has just come out, while on small screens we have Hercule Poirot: The London Case, in which you step into the Belgian sleuth’s tight patent leather shoes.

This is the second Poirot game from developer Blazing Griffin and French publisher Microids, coming just a year after the debut installment, The First Cases. Telling another original story, the sequel is an affectionate homage to Christie that looks and sounds wonderful in most respects, but, like the first game, still suffers from illogical and nonintuitive deductions and a lack of clever plotting.

As with its predecessor, The London Case occurs early in Poirot’s career, at some unspecified date around the turn of the century. Poirot, still with the police but already the finest detective in Belgium, is assigned to escort a priceless painting, The Penitent Magdalene, from the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels to the Royal Edward Gallery in London. But nothing is ever simple or straightforward for Poirot. He is, as one of Christie’s characters put it, “a kind of stormy petrel; where he went, crimes followed.” The painting is subsequently stolen at the launch of the art exhibition, to general consternation – and one of the people present must be the criminal. Was it the glamorous American actress, or her vain Norwegian husband? The mysterious Russian? The pompous bishop? Or the crusading politician? With the help of a certain Arthur Hastings, an employee of Lloyds Bank, Poirot swiftly discovers both the thief – and a dead body. The case becomes one of murder…

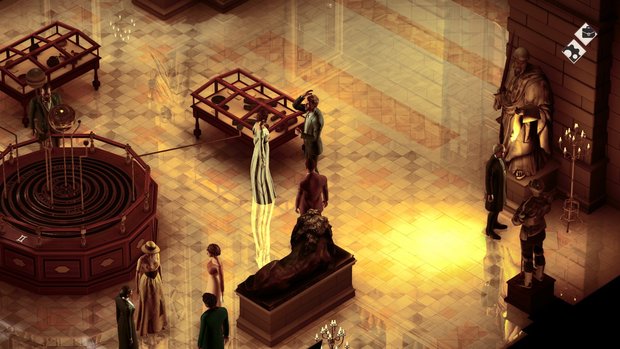

Before all that, the game begins with a prologue aboard a ship crossing the Channel. Poirot returns a cigarette case to a lady passenger and tries to identify who burgled her safe. This eases the player into the game and its tools. Like in The First Cases, the perspective is isometric, and the game employs a standard point-and-click, mouse-driven interface. Moving the cursor around the screen identifies any hotspots; clicking the left mouse button interacts with the object. The scroll wheel rotates the perspective of scenes and objects, bringing a new meaning to considering puzzles from a different angle. Clicking on some objects allows you to examine them in detail for points of interest; the game conveniently lists how many discoveries there are to find. This is meant to emulate Poirot’s orderly and methodical approach, but can seem like pixel hunting as you can spend a few minutes clicking everywhere on-screen.

The game reintroduces Poirot’s ‘mindmaps,’ which are meant to allow the player to think like the detective by creating complex mental diagrams and connecting the right pieces to solve the case. This also applies to gathering information about suspects, building character profiles to identify the culprit. But the connections are not always intuitive; for all Poirot’s urging you to think logically and employ your little grey cells, these sections often force you to guess in the method most random, n’est-ce pas? Fortunately, the right choices will glow if you make too many wrong choices.

Following the initial boat sequence, the rest of the game is set on dry land, in a handful of London settings: a museum, a theatre street, a bishop’s ‘church’ (cathedral, surely?), offices and apartments. The fashionable arty milieu recalls Christie novels like Lord Edgware Dies or Three Act Tragedy, but even more so her contemporary Margery Allingham’s Death of a Ghost: an art gallery with its flamboyant painters, social hangers-on, trustees, and independent women doing the work; crime at an exhibition opening; and forgery. A few of her Mr. Quin short stories aside, Christie rarely set foot in the world of art; she tended to commit her murders in big houses, villages, and abroad (especially the Middle East and archaeological digs).

Fittingly for a game set in the art world, The London Case is aesthetically pleasing for the most part. If the style of the David Suchet TV adaptations was 1930s Art Deco, this game shows more of a Belle Époque sensibility, from the curves and flowing lines of Art Nouveau to the angular style of the “moderns.” It is a transitional period: the gallery’s conservative trustees loathe newfangled approaches, while seemingly respectable politicians’ offices hold busts of Queen Victoria. The attention to detail is remarkable, down to reflections in the marble floor of the museum, puddles of water in the street, and shadows in the church. An underground cellar feels so real you can almost smell the dust.

Christie’s characters have (unkindly) been called puppets; here the suspects resemble waxen marionettes or claymation models. This is jarring at first – and distractingly aboard the ship, the people sway as if slightly tipsy – but you become used to their stiff appearance, even if the lip sync often does not match the speech. But the voice acting throughout is excellent, with a range of accents crossing the Atlantic and most of Europe – including, of course, Belgian. Christie’s dialogue was one of her strengths, as shown by the successful radio adaptations of her works and the popularity of her plays with amateur theatre groups; The London Case does not quite have Christie’s deftness and lightness of touch, but it is workmanlike and occasionally witty.

But does it work as an adventure game, or as a detective story? There are some unusual puzzles: in Chapter 1, an acquaintance challenges Poirot to work out which painting he has matched with which guest – a novel way of establishing the suspects’ personalities (narcissist, centre of attention, underdog, hard worker, etc.) – like Christie’s own interest in patterns and archetypes (fitting suspects and murders into nursery rhymes, for instance). Several puzzles feel like filler, however, such as finding a missing cat. Another time-consuming puzzle: to get a set of spare keys in Chapter 6, Poirot has to open no fewer than three safes and decode a couple of cryptic messages. There are more safes to open in Chapter 7, as well as a secret passage in the church to find. They feel more like roadblocks than organic parts of a mystery.

It’s fair to ask if the Agatha Christie whodunnit is even suited to adventure games. One would presume so – both are combinations of narrative and brainteaser, “complicated and extended puzzles cast in fictional form,” as the American detective writer and critic S. S. Van Dine argued in the 1920s. John Dickson Carr, one of the genre’s most brilliant practitioners, called the detective story “the greatest game in the world,” with the reader pitting his or her wits against the author’s, just as the player of adventure games does. Christie was the supreme literary conjuror: she laid her cards on the table, presenting the clues fairly, but in such a way that the reader’s attention was forced elsewhere. Carr admiringly called her “the female Sixteen-String-Jack, the original Artful Dodger: you must never take your eye off her for a second.” Then at the end, she pulled the rug out from under you, leaving you floored.

Yet how can the player of a computer game, controlling Poirot, be surprised? We have to puzzle our way, step by step, through the problem. Unlike a Christie novel, where major clues are strewn throughout the narrative from the start, and dangled in front of the reader who can turn back to check, the computer game advances, inexorably, and clues are discovered at later stages. This turns the game from a problem in deduction, a puzzle to be solved, into a procedural.

Here Poirot discovers clues to the perpetrator’s involvement gradually, including three right at the end of the game that confirm their guilt. It is clear from the two-thirds mark where Poirot’s suspicions lie, long before he assembles the suspects in the art gallery for his J’accuse! moment. As a result, The London Case lacks that characteristic ‘Of course, damn it!’ surprise that makes you want to kick yourself good and hard with your stoutest boots that Christie delivered so reliably and so remorselessly for so many years.

The clues aren’t particularly clever either. With Christie, the clues (a butler’s calendar, for instance, or a vase of flowers on a malachite table) have an obvious meaning the reader tries to puzzle out; at the end, their significance is revealed to be quite different; they need to be interpreted. Here, however, the game’s incriminating evidence is very straightforward. It’s all very competent overall – certainly up to the standard of recent Agatha Christie pastiches like Sophie Hannah’s – but it’s not as clever as a Christie homage should be.

Nor does the solution snap into place as satisfyingly as any of Christie’s. The essence of her work, as Robert Barnard (A Talent to Deceive) remarked, was her simplicity. The solution can be summed up in a single high-concept line: the narrator is the murderer; all the suspects are guilty; the victim did it; the detective did it; the impossible suspect (the person with the alibi) did it. They are solutions we may have never considered, but are inevitable in retrospect. Here the answer feels unsatisfying, perhaps because there is no sudden flash of illumination, or perhaps because any of the other suspects could be equally likely culprits.

Final Verdict

Hercule Poirot: The London Case tries to capture the spirit of Agatha Christie’s famous detective, but lacks Christie’s touch to fully succeed. It’s always a pleasure to join Hercule Poirot on a new case, joined here by Hastings for the first time in game form. And the presentation is largely excellent: background graphics, voice acting, and period atmosphere. But this is the frame for a rather average adventure game and an unsatisfying mystery. Too many puzzles disrupt the flow of the investigation, rather than enhancing it, while Poirot’s mindmap deductions, supposedly integral to the game, are not intuitive. Even the solution lacks ingenuity and surprise, so crucial to Christie’s works. But then Christie, the best-selling author of all time, was, in the words of a contemporary critic, “the greatest genius at inventing detective-story plots that ever lived or ever will live” – and that sets an impossibly high standard for any game to match.

Hot take

Hercule Poirot: The London Case is a mixed bag for fans of Agatha Christie and adventure games. They will be thrilled to put the little Belgian detective through his paces once again, but the mystery itself doesn't fully satisfy.

Pros

- Agatha Christie fans will enjoy playing Poirot in a new case

- Game captures turn-of-the-century aesthetics and atmosphere across a variety of London settings

- Excellent graphics and voice acting

Cons

- Some puzzles feel like filler that do not contribute effectively to the mystery

- Connections aren't always logical, forcing guesswork

- Procedural approach to discovering clues doesn’t feel like Poirot

- Final conclusion is less satisfying than Christie’s clever and simple solutions

Nick played his own copy of Agatha Christie – Hercule Poirot: The London Case on PC.

1 Comment

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Thank you for the review

Reply

Leave a comment