Windy Meadow: A Roadwarden Tale review – Sweeping changes made to worthwhile but very different visual novel spinoff

- 0 Comments

If you boot up Windy Meadow: A Roadwarden Tale expecting Roadwarden II, you’re bound to be disappointed. Like its predecessor, it is set in the fantasy realm of Viaticum, and while both games tell stories about working people struggling in a world that cares little for them, the similarities basically end there. Roadwarden excelled with its signature mix of versatile text-based roleplaying and open-ended exploration; Windy Meadow is a linear, puzzle-free visual novel. Roadwarden took place in the wilderness of a sprawling peninsula, with more quests, locales and storylines than one could see in a single playthrough; Windy Meadow confines itself to a single community, and a dedicated player can finish it in less than four hours. Look beyond those differences, though, and you’ll find that Windy Meadow is a rewarding spin-off whose slice-of-life story—about values, choices, and the unpredictable ways they shape one’s world—is worthy to carry the Roadwarden name, if not on quite the original’s level.

Windy Meadow takes place in the titular village, and each of its three main chapters follows a different resident who faces a crossroads in life. There’s Vena, torn between taking up the family profession as a hunter or seeking her fortune as a guard in the big city; Fabel, a disabled bard-in-training grappling with the prospect of a life on the road; and Iudicia, an apprentice herbalist sorting through her feelings as her wedding day approaches. Over the same five-day period, while the village grapples with the life-and-death consequences of its residents’ choices, these three must navigate a web of relationships, emotions and decisions to determine their futures.

The original Roadwarden was rightly acclaimed for the depth and quality of its writing; any follow-up, then, will live or die by its script. Windy Meadow tells a smaller, more localized story than the previous game did, confining itself to a short period in the lives of a handful of characters, but so much time, attention, and nuance has gone into each villager’s portrayal that it soon feels like we know and care about them. Vena’s many family members, for instance, might easily have blended together or veered toward the archetypal in the brief time we have to become acquainted with them. Instead, each of her relatives has a distinct character arc, from her stoic yet protective father Latro, to her willful, ailing mother Predi, to her younger sister Hostia, who’s rushing to grow up.

The supporting cast remains the same across all three chapters (plus an epilogue), but which side of them you see depends on who’s looking. Fabel, for instance, simultaneously fears and respects his mentor Nalia, a retired adventurer with many tales from the road and no appetite for her pupil’s excuses. Iudicia, on the other hand, sees Nalia as a surly, unpleasant drunk. A codex, accessible through the main menu, lists everyone in town along with your current character’s thoughts about them. Vena’s, Fabel’s, and Iudicia’s codices thus read very differently, and occasionally reveal secrets that won’t come up in dialogue. (Iudicia, for instance, knows something personal about Hostia to which Vena appears oblivious.)

The codex also contains explanations for a few key concepts essential to the setting. This will be helpful for new players, though veteran Roadwarden players will have no trouble recognizing Viaticum and its peculiarities. Windy Meadow may take place far away from that game’s untamed peninsula, but there’s no mistaking that they’re part of the same world. Fabel’s guardian, the local priest in the faith of the Wright, was once a roadwarden himself; the rough lessons he learned on the road allowed him to rescue his now-foster-son from the bandits who’d claimed both his parents and his legs. References abound to the same colorful menagerie that dogged your own warden’s footsteps: the nearby river is full of hungry saurians, while local farmers raise noble griffins alongside their sheep. The area’s deciduous forests are home to incongruous monkeys and apes, while a troop of sasquatchian goblins gathers in the hills above and threatens to descend on the village. Any attempt to eradicate the threat risks incurring the wrath of the herds, a phenomenon whereby the wilds rise up and destroy any settlement that grows too quickly at nature’s expense.

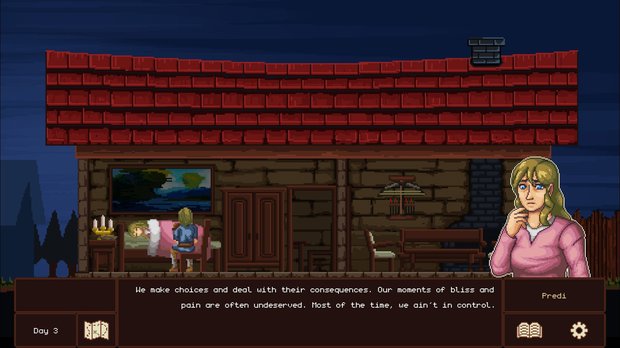

Windy Meadow is a true visual novel, meaning that gameplay consists entirely of dialogue choices; you’ll see the characters on-screen, with portraits appearing to denote who’s speaking, but you won’t control their actions or movements. This is, of course, a vast departure from Roadwarden, and it’s liable to kill some players’ interest entirely, but the format is a natural fit for a developer whose previous game succeeded largely on the strength of its writing. The narrative here may be smaller in scale, but the story, the characters and their dynamics are just as complex and involving as one would expect based on developer Moral Anxiety’s track record.

Life in Viaticum is precarious, and the village’s survival requires vigilance, forethought, and sacrifice. Vena, Fabel and Iudicia must each decide how to balance their desire for lives and futures of their own with their obligations to home and the people they love. Vena’s offer of employment with a wealthy merchant in the city would mean leaving her aging father as Windy Meadow’s chief hunter. Fabel, preparing for the solitary life of a traveling troubadour, is daunted by what feels like losing his family a second time. Iudicia must choose, as her mentor Salvia ages and grows frail, whether to continue living apart from the community or to try to integrate more actively by marrying a friend for whom she has no romantic feelings.

While all three characters are well-developed, with engaging arcs and vivid personalities, Iudicia’s chapter is where the game shines. Iudicia is a neurodivergent young woman in a society that neither understands nor seeks to accommodate her. She’s content with who she is, neither seeking to change nor to hide herself from others, but she recognizes that uncomfortable compromises may be necessary if she’s to serve effectively as the village herbalist. The game tweaks its own mechanics in subtle ways to embody Iudicia’s point of view, especially as regards her erstwhile mother and father. The thought of her birth parents, who gave her into Salvia’s care when they felt they couldn’t raise her effectively, frightens and confuses her; the world freezes and goes dark for a moment whenever they’re mentioned, and clicking their names in dialogue produces not a codex entry, as with other characters, but a flat refusal from Iudicia to even think about them. This small but impactful use of the interface helps bring Iudicia’s feelings to the fore in a way that’s only possible in an interactive medium.

The interface is built around conversation, with the only other buttons corresponding to your codex, a map of the area (entirely for reference), and the main menu. As you select dialogue options in conversation with others, you’ll make choices that determine what your character believes in, the dynamics of their relationships with others, and the direction in which their life is ultimately heading. Each chapter has two possible endings, with an epilogue in which all three protagonists must decide what comes next. This last decision is presented as an explicit either/or dialogue prompt—a design choice that, to me, took some of the wind from the story’s sails. Gameplay to that point has, after all, been about incrementally establishing your characters’ values; if you can simply discard them and choose the opposite path at the moment of truth, then what was the point? Your earlier choices would feel weightier and more significant if the totality of them determined your character’s arc. While you can, of course, select the option that’s most in line with how you’ve played, making it a discrete decision leaves the entire process feeling more cosmetic than consequential.

Further distancing the player from the action is the game’s uneven and awkward attempt to render characters’ speech in dialect. Characters in Roadwarden spoke with a unique affectation whereby words like little, even, and haven’t were rendered as lil, eva, and han’t. It took some getting used to, but in the absence of voice acting it helped to further establish the peninsula’s distinct character and history. Windy Meadow, likewise unvoiced, attempts a similar feat, but here it feels like an afterthought. The deviations from formal English are so minor and commonplace—about is always ‘bout, isn’t is ain’t, and apostrophes crop up on the ends of many –ing words—that they hardly read as a distinct mode of speech. It's only because they're applied so consistently that they even register, feeling less like true signifiers of a regional dialect than as a feature included hastily for the sake of congruence with the previous game.

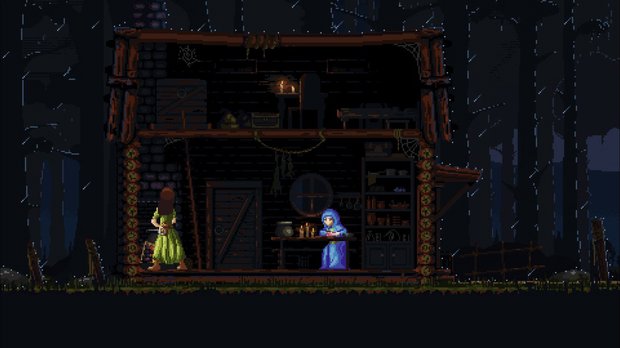

Visually, Windy Meadow does a solid job of bringing Viaticum to life, with lovely side-facing pixel art backgrounds and character sprites. Its use of color is especially impressive, subtly conveying information about each character and who they are via their associated palette. Salvia and Iudicia, for instance, live in a dark and rather dingy cottage in the woods, but the lively cerulean and lush green of their respective outfits serve as visual counterparts to the bright spots they represent to one another. Meanwhile, the hunters Vena and Latro dress in muted, utilitarian shades, clearly chosen for function rather than form, and Evolo, a wealthy transplant from the city, wears a royal purple unseen elsewhere in the village.

The environments, though non-interactive, are far from static; characters move about in lively fashion amidst crackling hearthfires and beasts of burden who fidget in their stalls. Now and then an animal or strange creature will amble past in the background, unremarked upon by anyone, to remind us that the people of Windy Meadow live side by side with wilderness. The game’s more stationary elements, on the other hand, don’t quite meet the same standard. The slideshow presentations that stand in for cutscenes are functional but unmemorable, and the smoother, more cartoonish-looking character portraits that appear in conversation are less impressively evocative than the detail-rich sprites.

The soundtrack features a series of stirring acoustic guitar pieces by the musician Doctor Turtle. These aren’t original to the game—the artist released them for free use on a Creative Commons license—but nonetheless fit remarkably well. The haunting, restive instrumentation renders tangible the central characters’ mingled reverence for their familiar surroundings and their longing to see the world beyond.

Final Verdict

Anything bearing the Roadwarden name has a high bar to clear, but judged on its own merits—as a visual novel—Windy Meadow is a clear success, albeit with a few more rough spots than its predecessor. Moral Anxiety’s rich, character-centered approach to storytelling is on full view here, and what the environments lack in interactivity they make up in personality and their ability to evoke a sense of place. Those who enjoyed Roadwarden for the depth of its setting and the quality of its writing will find more to admire here, though in a decidedly different form; newcomers to Viaticum will get a promising first look into what makes the place so special.

Hot take

Windy Meadow uses the visual novel format to tell a moving, thoughtful story about growth, decisions and community in a gorgeously realized setting. While not a modern classic on the scale of the original Roadwarden, those who go in with the proper expectations will find it a solid, rewarding narrative adventure.

Pros

- Subtle, well-crafted story and complex characters

- Multiple perspectives complement one another and grant a nuanced view of the setting

- The world of Viaticum is as intriguing as ever

- Lovely visuals and an effective soundtrack

Cons

- No real gameplay to speak of outside of dialogue sequences

- Final decision can mute the impact of player choice throughout

- Character portraits aren’t of the same quality as the other visual elements

Will played Windy Meadow – A Roadwarden Tale on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment