Desolatium review – Raw but intriguing Lovecraftian horror adventure designed like the node-based great old ones

- 0 Comments

I’d imagine the term “retro-style point-and-click adventure” would spur most gamers to think of something like Thimbleweed Park, a pixel art SCUMM homage mixed with modern sensibilities. For most the phrase probably doesn’t inspire the notion of a low-budget, first-person, node-centric adventure, à la Dracula or Necronomicon circa 2000. Despite having a devout fanbase, many games in this subgenre of horror adventures are deemed objectively janky, even if subjectively loved. Desolatium doesn’t reinvent the approach from this era, but rather seeks to replicate it, warts and all. It’s filled with curious design choices, and the production values are wildly inconsistent, and yet the game still manages to deliver a suspenseful and fairly satisfying adventure that genuinely feels two decades out of time and place.

The story begins with an amnesiac named Carter Scott awakening in a hospital room. Though the young man cannot remember how he arrived there, he quickly ascertains that this isn’t a normal facility, and he needs to find a way out – fast. Carter escapes from the holding room, discovering that he is being held in the headquarters of a group called Zotiques Enterprises. The building appears to be a medical facility at first glance, with offices, staff quarters, and examination rooms, but these inconspicuous-looking areas are adorned with macabre oil paintings and bizarre medical drawings, hinting at the organization’s true operations.

In fact, Carter has gotten himself mixed up with a doomsday cult looking to revive Cthulhu, though it’s not immediately clear how he lost his memory or what exactly his involvement in all this is. But Carter is not alone, as you’ll rotate through a few other characters pursuing the cult over the course of the game’s several chapters, including a professor named Sophie, a journalist named Christopher, and Carter’s boyfriend James. These characters all provide commentary (mostly in monologue form) about their goals in helping stop the conspiracy afoot, and how they are connected to one another is revealed gradually over the course of the game. The scattered information is a lot to absorb at first, but the story becomes much easier to follow after assuming control of each cast member a couple of times.

Your objective when starting each new chapter is not always apparent, but the environments typically funnel you through a linear set of areas with only one or two routes of travel before opening up exploration, ensuring you do not become overwhelmed with options of where to go. Though the game is relatively straightforward, there are plot points and items of importance that will impact which ending you achieve. In my playthrough, I evidently missed some of these according to the game’s achievement list, though I had no idea when or where I was making relevant choices or missing important routes, resulting in my getting an ending where things did not turn out well for Carter… or the rest of the world. The game saves automatically between each node you traverse, and though you can also manually record your progress at any point, there’s only a single save file for everything that is constantly overwritten.

Desolatium is a first-person, panoramic node-based adventure. You stand stationary at fixed points, but can freely rotate the view around you in 360 degrees, with a reticle in the centre of the screen changing to connote points of interaction like exit pathways, items that can be picked up, NPCs that can be spoken to, or hotspots that will trigger a comment or insight from your current character. There is a fair bit of pixel hunting, and while I was never stuck in one section for too long, I constantly found myself retreading areas in search of hidden clues or items I may have missed. There is a smart cursor but no hotspot highlighter, and some areas are so cluttered with objects that you will likely have to slow down and methodically scan, searching for which objects are interactive and which are just decoration.

One reason for this is the photorealism of the graphics. The settings are based on actual photos that have been rendered via the Unreal Engine, but nothing was done to make crucial items stand out to suggest that they can be interacted with. In Christopher’s first chapter, for example, you explore his publisher’s office, rooting through papers on his colleagues’ desks and others stored in the archives. The required documents spread around the office are camouflaged extremely well with the piles of non-interactive ones, meaning you will need to be incredibly thorough in running your cursor over every surface or point of potential interest.

The upside is that the photographs are often stunning, albeit completely static. The aforementioned Zotiques Enterprises almost looks like a normal place of business, but the not-so-subtle clues as to its macabre secrets create an absolutely chilling atmosphere. Once you make your way there, the island village of Innsmouth is dark and rundown, seemingly in a state of perpetual sunset, with the quiet streets leading to overgrown, ill-kept green spaces and vacuous streets. There is the occasional anomaly, like a texture seam running through the skybox in one area, but for the most part each scene effectively creates the intended immersion. When other characters populate these locations, however, the contrast in fidelity is stark. NPCs look typical of early 2000s pre-rendered games, appearing to rest atop the photorealistic backdrops rather than standing within them, sometimes resulting in them looking out of both place and scale.

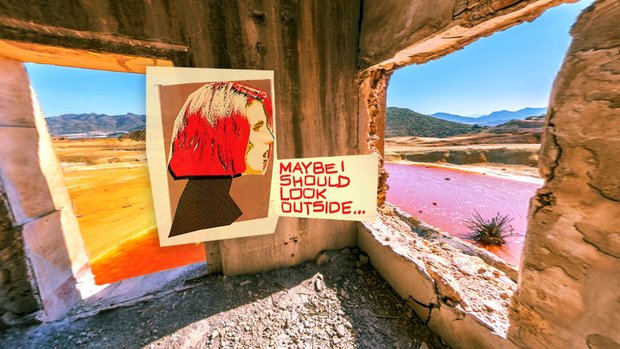

In a far more radical change of aesthetic, during conversation the game opts to utilize pulp-print-style collage graphics. The portraits displayed this way via dialogue boxes often look completely different from characters’ in-game models, especially on Innsmouth. Desolatium also contains a select few animated cutscenes using these portraits, as well as more ambitious ending sequences that are almost fully animated. Though the different looks work well enough on their own, switching between them can be jarring at times, though it does add to the game’s budget-style “indie” charm.

Another issue arises in how pathways are marked out. When moving your cursor over an exit, it will change to a series of footprints. However, these pathways are not always evident from the angle at which developer Superlumen has opted to situate your vantage point. A hallway in the game’s third chapter, for example, allows you to travel through a door almost completely obstructed from view, around a corner, leading to still more pixel hunting just for exits at times. When exploring Innsmouth, there is an obvious footpath leading straight ahead, as well as a small hole in a bordering fence leading to another route, but due to their close proximity it can be hard to tell that they’re different passageways.

The awkward framing of scenes is a constant issue, both in terms of environmental readability and in keeping one’s bearing due to a lack of landmarks indicating where you came from. Often, one hallway or passage has no visual connection to the previous area, making it hard to tell which door or street you just arrived from. A map or on-screen subtitles stating which area you occupy and where other routes lead would have helped alleviate some of this frustration, though with the areas being relatively small and few in number within each chapter, it may also have made the game too easy. Part of Desolatium’s challenge undoubtedly stems from its reliance on pixel hunting, which is something to be forewarned about going in.

The quality of voice acting is another area where Desolatium's roots are visible. Though none of the actors perform their roles poorly, the deliveries are almost always over the top, to the point of being nearly parodic. The subtitles also slightly differ from the voiced script from time to time, and there’s at least one instance where the grammar used is incorrect, though it isn’t hard to infer what is meant in context. Music is reserved, though melancholic and foreboding instrumentals play in almost every area, giving the game a suffocating density of horror in the best way possible.

Inspired by H.P. Lovecraft, the game poses no real risk of death, jump scares or game overs, though you can potentially make choices, purposely or not, that will lead you to one of the aforementioned “bad endings.” Instead, the quiet and still framing of each scene coupled with the music creates a constant sense of dread. Whether the cult is in fact able to tap into some otherworldly power and summon sleeping gods, or whether they’re just a bunch of well-organized lunatics, isn’t revealed until late in the game, and this uncertainty effectively builds suspense throughout.

Desolatium’s inventory system is streamlined into two categories: Notes and Objects. Notes are things like letters and pictures you find throughout your adventure, which may contain clues to puzzle solutions or may simply be worldbuilding pieces. Objects, on the other hand, can be used in the environment or with other items. Your inventory never gets too crowded, and anything you find is generally used quickly to solve a puzzle, being removed from your inventory thereafter. Notes do pile up, however, and with Christopher in particular, there is a lot of information to process.

Puzzles are creative and varied, sometimes being simple lock and key situations while others require pattern memorization or code inputs, like a cryptex password or a mechanized lock opened by way of inputting sailing directions via a directional knob. Audible cues often denote the discovery of a vital clue or document, letting you know you are on the right track.

There are some inconsistencies in how items are applied to puzzles. For example, at one point James attempts to sneak into Zotiques Enterprises, but attempting to use a stolen ID badge on the security guard at the entrance does nothing. Instead, you have to speak to him and then select the conversation choice indicating you have the card in your possession. Yet for most other puzzles, you simply drag the item from your inventory to where you wish to use it, like later in the same chapter when you offer to get a different security guard a coffee, then simply hand him the beverage without engaging in conversation.

While some puzzles are quite well-constructed, a select few duds stand out, like a particularly funny instance at Innsmouth. Sophie enters a bar to buy a bottle of whisky for an informant, but the bartender refuses to sell her any, stating that he doesn’t like outsiders. He then begins telling Sophie, for no good reason, that the power keeps going out, forcing him away from the bar and to the back room. Sophie notes the bar’s fusebox outside before entering the bar, and the tool you need to open and remove a fuse is – hilariously – sitting on the counter right next to the bartender. The plan falls together all too easily, temporarily taking away some of the suspense from exploring the peculiar town.

Final Verdict

When it comes to adventure games, “old-fashioned” can be a nice way of saying unforgiving and outdated, and in many ways that suits Desolatium but I can genuinely say that I enjoyed most of my time playing it. Even with some rough edges, its playability makes it an easy game to recommend, though only fans of this node-based, point-and-click horror subgenre are likely to find any joy in its bizarre pleasures. Desolatium was crowdfunded through Kickstarter, and it certainly feels like one, being aimed at a very specific audience. It’s not for everyone, but it isn’t supposed to be, so you may want to try out the free standalone prologue for a taste of what to expect. If this style of pixel-hunting, pre-rendered horror appeals to you, Desolatium should be worth investigating.

Hot take

Desolatium is an unapologetically old-school node-based adventure in the vein of turn-of-the-millennium cult classics like Dracula. Its mix of wildly different art styles doesn’t work as well as it could, but those who don’t mind a bit of pixel hunting will likely enjoy its budget presentation, generally solid puzzle design and atmospheric story.

Pros

- Varied puzzles

- Foreboding, atmospheric music

- Interesting horror-themed plot unfolds gradually from the perspective of several characters

Cons

- Characters don’t seamlessly fit into the photographic environments

- Node-based navigation can be confusing

- A fair amount of pixel hunting required for both items and exits

Drew played Desolatium on PlayStation 5 using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment